AN OBJECT-ORIENTED FEMINIST APPROACH TO SPECULATIVE AND CRITICAL DESIGN

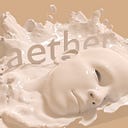

Speculative and Critical Design (SCD) has a history of being restricted to privileged western and European countries with the ideologies of a “better society” in mind. Despite SCD’s aims to challenge our assumptions of everyday life, it does so purely on an aesthetic level, and one that ultimately discredits people marginalized in society. With the prevalence of unnecessarily gendered marketing strategies, there is an influence on design culture which in turn influences the way our society perceives itself. Since design is ideological and informed by values based on a world view, as Dunne and Raby state, it is important to consider what it means ideologically if designers are willing to propagate gender discrimination and exclusion through product design and interaction. Through an object-oriented feminist approach on SCD, I will briefly talk about the phenomenology of object categorization and the state of “being” in terms of a collective non-corporeal future, as well as the real and unreal taxonomy of queer and femme bodies as objects.

Object Oriented Feminism stems from Object-Oriented Ontology, a Heidegger-influenced theory that rejects prioritizing human existence over non-human objects, making claims about the equality of object relations. It is ultimately all about objectification. It is viewed as a subset of speculative realism and states that objects exist independently of human perception, in contrast to a Kantian view of the mind constructing the human experience. It is essentially a form of non-anthropocentrism; the world consists exclusively of objects and treats humans as objects like any other, rather than privileged subjects. Object oriented feminism approaches all objects from the inside-out position of being an object too. It foregrounds this concept in three main ways, through politics, engaging with histories of the treatment of minorities, erotics, using humor to make the unseemly connection between objects, and ethics being in the right by being “wrong.” As Katherine Behar states, art and feminism have had long standing engagements with the notion of human objects.

This object-centric argument brings us to the questions of what constitutes a body? What constitutes an object? What animates an object and what objectifies a human? To further this question, how do we categorize the concept of gendered objects within the scope of Object-Oriented-Feminism? The separation of gendered objects throughout our society emphasizes a distinctive binary of the feminine and masculine. But through the lens of being an object, what actually defines masculinity and femininity? According to Riviere, there is not any particular difference between the “genuine” womanliness and the masquerade. Femininity is a performance. Stephen Heath points out that “in the masquerade the woman mimics an authentic womanliness, but then authentic womanliness is such a mimicry, is the masquerade; to be a woman is to dissimulate a fundamental masculinity, femininity is that dissimulation” Therefore the masquerade shows that the woman exists and simultaneously doesn’t exist. “A woman, or fractured being, is defined only by a phallic lack.”

This brings us to the idea of Meinong’s Jungle, a different type of object categorization, one that is explained by Dunne and Raby here. Alexius Meinong’s Taxonomy of Objects talks about separating objects into things that exist, and things that do not exist, or things that “have being” or things that “do not have being,” These categories are divided into subcategories of real and ideal, objects that have non-being, and objects that are not determined with respect to being (see chart). It is the idea that non-existent objects and even impossible objects such as round squares should be included in any proper taxonomy of objects. The majority of representation of unconventional bodies in the media and in SCD proves this to be so. Through an object-oriented feminist lens, politicized bodies of femme, queer, trans, or any other lgbtq+ persons, in our society must be “non-existent,” or “non-real” objects. The idea of a body rejecting the conventional ontology of the feminine and masculine must only exist as non-being, as proven by representation in the media. A round square has the properties of being round and not round, but this is not to say that it can’t exist. In Meinong’s taxonomy this exists as Contradictory objects — they have constitutive properties that are in some way in conflict. “A round square can be both round and not round — in fact it has to be both round and not round in order to be a round square. But, to say that it is the case that the square is round and it is not the case that the square is round, is contradictory.” These same properties can be applied to femininity and masculinity, a binary that can “contradictorily” exist within the confines of Meinong’s Jungle.

In a world where objects are defined as “all things that can be the targets of mental acts,” these objects exist and have “outside being. ``What does it mean when we anthropocentrically view objects as only constructed in the human mind? In a speculative future that is non-corporeal and collectively assimilated into a digital and virtual consciousness, the ideas of entities are obsolete. What will this entail in terms of recognition of bodies, entities, objects? This brings us to the concept of a digital ontology. Today, SCD, or even any speculative methodology, rarely ever talks about electronic artifacts in gender roles, or how technology intersects with gender oppression. Will there be a shift in the recognition of items that are targets of mental acts? How will we distribute the democratic ideals of a non-gendered, non-corporeal system throughout a cybernetic society?

Meinong’s jungle poses a speculative alternative to object ontology which lets us analyze objectified beings through the lens of non-existence. Sarah Ahmnd, in Queer Phenomenlogy rejects the idea of a universal experience underlining the importance of understanding power systems embedded within objects. Both Meinong and Ahmed point to specific methods of power inside systemic interconnections. These lenses allow us to pose a speculative future of a new digital ontology, and dream of an age of digital manuscript in which the ideas of entities are obsolete. Instead, we think of “Us” as the entity, digital network, AI body; a re-construction of synthetic neural networks where object recognition is posed as our un-real existence, our non-existent bodies.